Have you ever heard of the teletransportation paradox?

If you’ve consumed any science fiction media in the 20th or 21st centuries, there’s a good chance you’ve encountered a version of it.

But it goes something like this.

Imagine a scientific entrepreneur builds a way for us to all get to Mars. In this scenario, planet Earth is on its last legs, Mars is terraformed and beautiful, and we all gotta go for our safety. The apparatus taking us there isn’t a space ship; it’s a sophisticated teleportation machine that will immediately send a person from one planet to another. No vomit inducing launches through the atmosphere, no cramped stressful conditions traveling through space; just step on a teleport pad and find yourself in a new world. Sounds great, right?

There’s a catch. In order to use the teleporter, you have to sign a waiver that you understand the mechanism behind how it works. You see, it isn’t literally transporting you, intact, how you are. Instead, the machine breaks you down at the atomic level, recording your physical composition in exact detail, from the proteins that make up your DNA to the neurons that make up your consciousness and memories. This information is sent to the corresponding machine on Mars, and the atomic building blocks are also sent at the speed of light. That machine then uses the information and the atoms to rebuild you exactly as you’re meant to be.

Many people have done this before you, and by all reports they’re happy and healthy on Mars. They have all of their memories, their identities are intact, they seem to be the same people they’ve always been. Knowing all this, do you use the teleporter? Do you step on the pad, knowing that you’ll appear safe and sound on the other side? Or do you refuse, knowing that using the machine is certain death, and it will only be a copy of you emerging on Mars?

If you said yes, you would use the teleporter, let me complicate things for you. You keep reading the waiver. Apparently, 1/10,000 times something strange happens. The teleportation machine needs to establish a secure connection to its counterpart on Mars. In cases where it cannot, the person entering the Earth machine is rebuilt as they were — still on Earth — using stock atomic material. It’s a safeguard for if their atomic building blocks are lost during the transfer. Okay, kind of scary. But you keep reading. There’s a 1/1,000,000 chance something even stranger could happen.

Something scarier.

1/1,000,000 times, this could happen. Earth’s teleportation machine sends your information and atomic building blocks over to Mars, but loses connection, and can’t confirm that they got there. So the Earth machine uses stock atomic material to rebuild you as you were. Meanwhile, on Mars, your information and atomic building blocks do get there, and the Mars machine completes its build. Now there’s two of you: one on Earth, one on Mars.

How’s this possible? Surely it couldn’t be; they should redesign the process so that such a thing cannot happen. And yeah, that’s all in the works, but for now this result is possible, if unlikely.

Do you step in now?

If you do, and the 1/1,000,000 situation occurs, who is the real you? One could say the Mars version is, since it’s made up of your actual material building blocks that travelled there. But the Earth version remembers making the choice to teleport, remembers coming out still on Earth. Don’t they deserve a life, a second chance to make the journey? But then, they already did, didn’t they? As far as the Mars version is concerned, they did make that journey successfully. This explanation, of course, won’t be much solace to the Earth you.

This thought experiment challenges us to take stock of what makes a person that person. I find it fascinating, and plenty of scifi writers doo, too: the concept has inspired countless stories, movies, and TV episodes over the years, from The Outer Limits (“Think Like a Dinosaur”) to Star Trek (early on in TOS, Dr. McCoy is distrustful of the teleporter, convinced it actually kills whoever uses it. Later in TNG, Geordi LaForge actor Lavar Burton directed the episode “Second Chances,” where a transporter accident results in two versions of Lt. Riker).

My favorite version of this trope, though, appears in the comic book Rom Spaceknight.

For the uninitiated, Rom is a comic book about a “Spaceknight” from the planet Galador. On Galador, men and women give up their humanity to become Spaceknights, powerful cyborgs designed to fight the cosmic menace of the Dire Wraiths, an evil alien race with the ability to change their appearance at will. The Dire Wraiths have infiltrated Earth: our governments, our militaries, even an average town in West Virginia. They could be anywhere. They could be anyone. Rom, with his trusty Energy Analyzer and Neutralizer ray, can detect Dire Wraiths and exile them to the plane of Limbo.

A lot of people love Rom. I love Rom. He’s cool. Most of it is because Sal Buscema and Steve Ditko are really good at drawing robots fighting weird monsters, but there’s also something deeper going on. Rom Spaceknight is a story about a soldier at risk of losing himself during war. As the story goes on, it seems more and more unlikely that Rom will be able to both keep his humanity and defeat the Dire Wraiths (add to all this the fact that Rom started out as a toy for children, and there’s a lot to say about the boy to military pipeline, but that will have to wait for another time).

Since the original series runs into the 80s, it was only a matter of time before this metaphor for the psychology of war took us to the USSR. Rom finds himself there after an adventure with Dr. Strange. Their mystical off world team-up over, the Sorcerer Supreme gives Rom a lift to a place home to the highest concentration of Dire Wraith activity on the planet: the Khystym region of the Soviet Union.

Rom probably expected a place like one of the other locations he’s visited on Earth so far: suburban houses, urban cityscapes, idyllic countrysides, or even ancient castles.

What he sees instead is a horrifying toxic wasteland.

The Kyshtym disaster of 1957 is now overshadowed by the more recent, and more devastating, Chernobyl disaster, but in 1983 — the year Rom #42 published — it would have been the worst nuclear accident in history (it is still the third worst, in terms of population impacted). A tank of poorly stored nuclear waste exploded underneath the Mayak plant, jettisoning radioactive particles across more than 52,000 square kilometers, potentially contaminating the homes of the 270,000 people who lived there. The accident was largely covered up, but in the 18 – 20 years that followed the world at large learned the details of what happened there.

So the scene of horror that confronts our hero may be understood as an informed exaggeration, and given the political climate of the Cold War it may not be surprising that Mantlo chooses this scenery as Rom’s introduction to Soviet Russia.

What might surprise us is what Rom comes across next. While wandering through the desolation, Rom eventually comes to a much different scene. An Oasis. Here, the terrain is vibrant and beautiful, the flora lush and colorful, and there are sparsely clothed (think Tarzan) people dancing, happy to be alive. As soon as they see Rom’s silverly form, they adorn him with flowers, and link hands in a circle around him.

They introduce themselves as “the Dead.” When the radioactivity drove them from their homes and brought them to the brink of death, they wandered, lost, until a mysterious voice beckoned them into a cave, and promised to make them whole again. So here they are. They invite Rom to do the same.

He accepts.

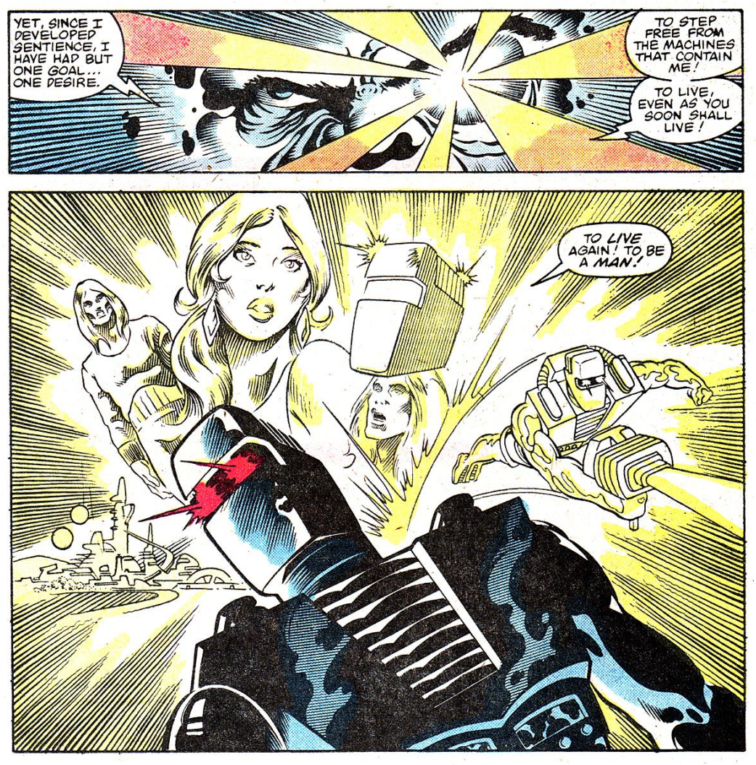

He enters the cave, meets the Giver of Life — actually a Marvel d-lister named Quasimodo — and agrees to a bargain: if Rom gives Quasimodo his shining Spaceknight body, Quasimodo will clone him into a new body of flesh and blood, as he’d done with the others outside the cave.

Rom is now human, at last. Issue 42 ends with him waking up in the body of a man, feeling more alive than he’s felt in years. A smile spreads from cheek to cheek as he clasps his hands to his face, filled with joy. Rom runs out from the cave, ready to live his life. There’s one final page, where we see Quasimodo now inhabiting the Spaceknight body, colluding with none other than the Dire Wraiths.

Personally I wonder if the comic wouldn’t be better without this final teaser, or any appearance of the Dire Wraiths. What if we believed that Quasimodo has the best of intentions? How eerie would it be to see our hero unceremoniously give up heroing for good? What a punch to the gut to see him wake up a happy man, unburdened by the responsibility of his endless war, the driving force of the story’s drama gone in an instant?

Such a moment of doubt isn’t unprecedented in comics, but it’s rare to see one so apparently complete. When Spider-Man throws his suit in the trashcan in Amazing Spider-Man #50, he could still go back to get it. He still has his powers, he’s still fundamentally the same person he was before, it’s just a matter of time before he works out his issues internally.

Rom, however, has given up everything that allowed him to fight the Dire Wraiths. We have no textual reason to believe the process can be reversed. Rom is a Spaceknight no longer.

What if this were the final issue of Rom Spaceknight? Imagine: as recently as the beginning of #42 Rom was dedicated to fighting his enemy wherever he could find them, but at the first opportunity he turns his back on this quest for his own selfish desires. What kind of hero is this?

One who’s been through it. Rom has always waxed romantically of missing his humanity, but he’s also always been dedicated to saving people from the enemy he’s uniquely built to defeat. After 40 issues of comics, he’s gained victories, suffered set-backs, experienced great loss. No matter any of that, the Dire Wraiths remain. Rom is no closer to winning than he was at the beginning, so why should he bear all the weight of this fight? Why shouldn’t he seize this opportunity while he can?

I feel for the guy, I do.

Spider-Man throws away his costume because of a lack of appreciation for what he does. For Peter Parker, being Spider-Man means a sacrifice of his time and personal life. He constantly needs to choose between stopping villains and meeting his social and family obligations. To give up his alter ego means freedom to live his life as a regular person, and freedom from undeserved scrutiny.

For Rom, the sacrifice is greater. There is the sacrifice to his personal life — he put a relationship on pause to become a Spaceknight, and in the years since his lover has died — but there is a physical sacrifice, too, one that comes with deep traumatic scars. His very body was disassembled, pieces of it grafted into a machine, while the rest was stored away. Once there was hope to use this stored flesh to become human again, but during a tragic series of events it is now destroyed.

Rom often calls his Spaceknight body “unfeeling.” While it’s clear he has access to enough sensory information to navigate the world, he seems to be lacking the capacity for sensual pleasure. And whether because of this deficiency or more psychological reasons, Rom is convinced he’ll never be able to make emotional or romantic connections as long as he’s in the Spaceknight form (did I mention Rom started out as an action figure?).

What breaks Peter Parker out of his moment of heroic denial is a reminder of why he became a superhero in the first place. For Rom, the impetus is much darker, a matter of survival. Rom spends a portion of issue #43 frolicking in the lush paradise outside the cave, until he finds the corpses of the dancers he’d seen healthy only hours before, their bodies scarred and deformed from radiation poisoning. Soon after, Rom’s body begins to show signs of the same.

Rom rushes back to the cave. An eventful series of happenings result in the defeat of Quasimodo, and the retrieval of the mass of flesh previously grafted to the Spaceknight body. In issue #44, a weird lil’ guy named Gremlin is able to put the original Rom back together again.

But what of the new Rom, the human Rom, the clone? Nothing is left for him to do but die from radiation sickness. He has parting words for his former self — his future self — before he goes.

“You are a man…in cyborg armor! You live! Living…you are capable of…love. Those are the two greatest gifts…that any…man may know! Embrace them…you who are fortunate enough to have them! Hold them tightly…and for my sake…do not squander either.”

Rom Spaceman, to Rom Spaceknight

Rom’s moral failing is resolved. Or is it? By extension of a new life, Rom has learned that it’s better to live a noble life in a body of metal than to have no life at all. This Rom’s second chance at humanity was short and purposeless, but may have given him the perspective he needed. Unfortunately, it required dying.

This places the original Rom in a unique position, to have his own self impart upon him the lessons of mortality. Will he take this lesson to heart without having experienced it himself? Not right away. Rom remains pessimistic after this issue, the change of heart only present in the fleeting life of the clone gone from the world.

People change, constantly. This simple fact leads many philosophers to believe that our idea of a self is nothing but an illusion. David Hume famously concluded that there was no self, since none of us can say we perceive any constant feature within ourselves which we could call that.

There we find the bleakest answer to the teletransportation paradox: neither of the reassembled persons are the real “you,” since any “you” that exists dies from moment to moment, left behind as the present becomes the past. Rom’s clone isn’t the same ROM as we knew him, but neither is the Rom reassembled by the weird lil’ guy. Experience changed him as it changes us all; we’re helpless in the wake of time and memory.

There’s another interpretation, to say this is the most liberating answer to the paradox. If identity isn’t constant, then there are no limits to who we can be. This freedom is terrifying, nearly paralyzing, which is why we retreat to our notions of self built upon memories and physical signifiers.

For a man trapped in the body of a machine, tormented by his memories of humanity, it may be just the freedom he needs.

— Ben Rathbone is the creator of this site, and its only writer. Don’t find him anywhere.

Leave a Reply