Thomas Carlyle said “the history of the world is but the biography of great men,” a banger, if contentious (and sexist), quote if there ever was one. I can say something similar: “the history of 80s nerd shit is but the meeting of two men in a bathroom during a party.” At least, that’s the case with G.I. Joe.

The legend goes like this: Jim Shooter, by then editor-in-chief of Marvel Comics, exchanges pleasantries with a Hasbro executive in the little boy’s room, and they get to talking. As fate would have it, Hasbro is trying to find a loophole that will allow them to use animation to advertise their line of G.I. Joe action figures to children, and comic books may be the key. The FCC / FTC prohibit the use of cartoons in toy commercials, but there’s no rule against cartoons advertising comics. So if Marvel were to publish a G.I. Joe comic book, both companies could benefit from an animated commercial.

Shooter agrees. Writer Larry Hama develops the toy franchise into a fleshed out story concept, including a roster of villains called COBRA. Hasbro gets their way and develops a cartoon thanks to the comic book loophole, and Marvel benefits too: their G.I. Joe comic is a bestseller thanks to the franchise’s television presence. A few years later, Hasbro and Marvel repeat this maneuver with another franchise that continues on to this day: Transformers.

Two of the biggest nostalgia powerhouses of the 80s lived and breathed thanks to Jim Shooter’s Marvel Comics, but they weren’t the first to do it. Shooter becomes editor and chief in January 1978, and nine months later Micronauts #1 hits the stands. Formulaicly, Micronauts strikes the same beats as G.I. Joe and Transformers: a colorful assortment of aesthetically distinct heroes and vehicles face off against a colorful assortment of aesthetically distinct villains and their vehicles, all based on a line of toys originally created by Japanese manufacturer Takara, and afterwards licensed by American company Mego.

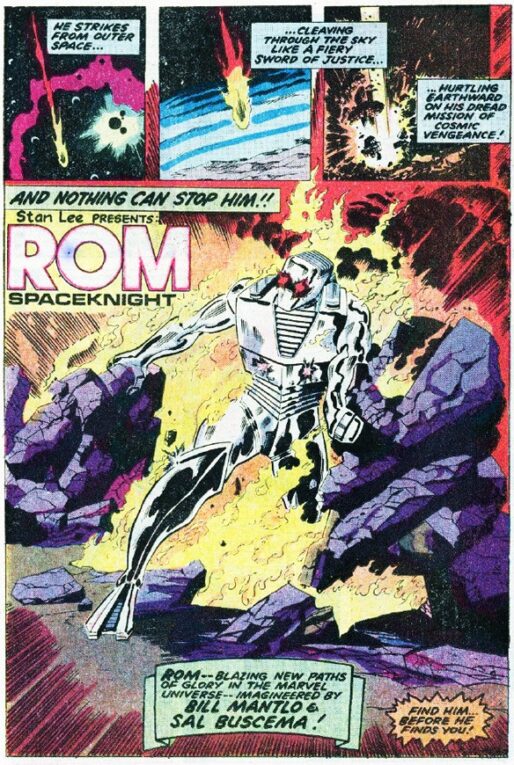

Another toy comic drops a year later, in September 1979, still 2 years before Shooter’s men’s room business deal. Rom Spaceknight is different from his more popular successors. For one, the toy itself sucks. Board game company Parker Brothers was only willing to put moderate investment into their first attempt at an action figure. While the Rom figure possessed some cool features like LED lights and electronic sounds, it suffered from a distinct lack of articulation and opposability compared to its peers.

More importantly, Rom came by himself, with no line of allies to support him or enemies to fight. It was mostly left up to writer Bill Mantlo (who also penned Micronauts, and would later co-pen the first few issues of Transformers) and artist Sal Buscema to dream up the Spaceknight’s friends and foes. Dream up they did, but despite it all the character doesn’t stray far from this solitary origin for a large part of his series. Rom is a story of a man trapped inside himself. No matter how many friends he meets on his journey, he struggles to connect with his own humanity because of what was taken from him.

Yes, despite a rich supporting cast, Rom, fundamentally, is alone. In this way he embodies a Western, American myth archetype: the lone, complicated individual pitted against the faceless, exotic horde.

Rise of the Action Figures

The first “action figures” were technically the very first G.I. Joe figures in 1964, as Hasbro invented the term to separate it from the dolls they sell to girls.

G.I. Joe initially raked in the cash, until sales faltered in the face of the Vietnam War by the end of the decade, as parents hesitated to buy military toys for their kids. Hasbro regained some ground by pivoting the line away from war, and by 1970 the Joes were now labeled an “Adventure Team.”

Then, Star Wars hit theaters in 1977. By Christmas the following year it seemed like every boy in America placed the movie’s action figures on their wish list. Even before Star Wars, G.I. Joe had pivoted to Sci-Fi, introducing a line of alien villains for the Joes to fight named the Intruders: Strong Men from Another World.

So when it came to action figures, space was now the place to be. Parker Brother’s move into the action figure market in 1979 with a space age hero makes perfect sense. Rom was an experiment, both because PB had never sold an action figure before, but also because electronic toys were still a pretty new concept. PB wasn’t willing to assume a whole lot of risk, and manufactured the toy as cheaply as they could. Time magazine predicted that the most exciting place the toy would end up would be under the sofa, and by 1980 it appeared they were right; only between 200,000 – 300,000 units sold in the US.

But while the toy failed by the beginning of the 80s, the comic continued well into the decade. As far as what Bill Mantlo and Sal Buscema had to work with, here’s the accessories boxed in with Rom: a rocket pack that makes roaring sounds, a respirator that makes breathing sounds, a translator that makes beeping sounds, a neutralizer that makes static sounds, and an energy analyzer that makes different, chiming, static sounds. Most of these flash red LED lights when activated, as do his eyes and two lights in his chest. You can control which accessory to activate using two buttons on the toy’s back.

In addition to the figure itself, Marvel had access to a promotional video PB aired at the 1979 Toy Fair. In it is the first mention of the Spaceknight’s enemies the Dire Wraiths, described as “evil magicians” who “can assume any form they wish.” We also learn the functions of Rom’s various gadgets: with the Energy Analyzer Rom can “see through appearances and determine the true essence of any being,” and the Neutralizer can “disorganize any molecular structure.” We know Rom is part of an order of knights who defend truth and justice, and that the Dire Wraiths fear Rom more than all the others.

These details, by themselves, do not a comic series make, but it was a decent enough start to get Mantlo and Buscema rolling. They created Rom’s planet Galador, a platoon of fellow Spaceknights, and a roster of supporting characters — including a love interest — who all live in the town in West Virginia where Rom first arrives. He’s traveled to earth to stop a Dire Wraith invasion; in the comic the villains are an alien race, and after they failed to conquer Galador they spread across the galaxy to find new planets to ravage.

But by far the most interesting addition they brought to the table is Rom’s origin. It is clear by design that Rom is probably a robot or cyborg, though in the lore provided by Parker Brothers it isn’t apparent whether his whole race are machines or whether he is a biological being wearing some sort of military apparatus. The comic’s answer to this is something far more fascinating. In order to fight off the Dire Wraith invaders, Galador subjected volunteers to an inhumane process whereby they’re made into cyborgs; a portion of their flesh and blood bodies are removed and fuzed into a personalized war machine. The remaining portion of their bodies remain in storage, with the promise that they can be restored to their original humanity once the war is over.

Rom, like all Spaceknights, literally must sacrifice his humanity to fight Galador’s enemies. The metaphor hits you across the face, and serves to bring Rom, an action figure created 10 years after war action figures started to lose popularity, full circle. The Vietnam War created the market conditions that birthed him, and years after it ended comic book writers thought they were ready to write about it.

Morality Play

War makes even good men lose their humanity. This theme — blunt as it is — has the potential to elevate what would otherwise be a simplistic science fiction action adventure tale of good versus evil. It does so sparingly. While Rom benefits from a complicated inner conflict, he never once doubts the absolute evilness of the entire race he fights, and the comic never gives pause to question whether he’s right, the reader left to assume that he must be.

In this, Rom was not unique, in toys or comics, and in comics there was a specific reason for it. The Comics Code Authority — established in 1954 — enforced a multitude of general standards that strictly censored a medium which beforehand enjoyed no oversight at all. These standards included “Policemen, judges, Government officials and respected institutions shall never be presented in such a way as to create disrespect for established authority” and “In every instance good shall triumph over evil and the criminal punished for his misdeeds.”

These and other standards particularly targeted the crime and horror comics popular of the day. The fear was that these comics were psychologically damaging to kids, and would influence them to commit violent crimes themselves. However if comics did indeed wield undue psychological power over children, then the code introduced a new problem. The world now presented to children on the page was black and white, one where authority figures like the police, judges, and government were innately good, and those who oppose them innately evil.

The funnybook morality panic behind us after the 50s, a new psychological zeitgeist would sweep over our young boys in the 80s, slowly building in the background, largely hidden from sight. Except this one was intentional, real, and no one panicked.

After Hasbro’s success turning G.I. Joe into a cartoon that would advertise the toyline for years, Mattel developed their own action figure line they would market to kids, and went so far as to conduct focus tests on boys to find out what makes them tick. They named their toy “He-Man” so as to sound as masculine as possible. When boys played with He-Man in these focus tests, they often ordered the figure around. Execs took from this that boys were attracted to power, and brainstormed a name for their line that exuded this. They chose “Masters of the Universe,” inspired by Tom Wolfe’s nickname for Wall Street suits in “Bonfire of the Vanities.” A Masters of the Universe comic and cartoon were not far behind.

Action figures now dominated the play spaces of young boys in the 80s American household, between G.I. Joe, Transformers, and the He-Man and the Masters of the Universe. More would come. These toys gave kids something to latch onto; the advertisements they saw onscreen served as models to structure their playtime. As a result creative free play — an activity psychologists agree is healthy for children — became that much less creative.

These characters had a profound emotional impact on those who grew up with them. Hasbro found this out the hard way when they pushed for Optimus Prime’s death in the animated Transformers movie, to make room for a new toy character to sell. Crying kids left the theater, disconsolate boys locked themselves in their rooms, and angry parents wrote in to Hasbro in droves (Hasbro originally planned to kill off the G.I. Joe character Duke next, but were able to switch course during the production of that movie).

While Rom as a toy never took off in the same way as his contemporaries, the same dynamics are built into his comic book DNA. Rom is an action figure on the page — a very cool action figure, more opposable and versatile than the toy ever was capable of — and an action figure needs someone to fight.

Thank you to Brian “Box” Brown for his book The He-Man Effect: How American Toymakers Sold You Your Childhood, which served as the source for most of this article’s information. Any errors are my own.

This article is the first in a 4-part retrospective on the original Rom series. Here, we introduced Rom within the context of the toys and comics of the time. The next three parts will be about how Rom explores dehumanization in war. Part 2 and Part 3 are about how the series presents its villains the Dire Wraiths. Part 4 will be about disability and war, and will explore how Rom seeks to portray the psychology of mentally and physically wounded soldiers and veterans. Also see Who is the Real Rom Anyway?

— Ben Rathbone is the creator of this site, and its only writer. Don’t find him anywhere.

Leave a Reply