This article is the second in a 4-part retrospective on the original Rom series. Part 1 introduced Rom within the context of the other toy comics of the time. I would suggest you read it, but you’ll be perfectly fine starting here too. Also see Who is the Real Rom Anyway?

“Far, far, away, in another galaxy, the knights of the Solstar Order, defenders of justice and truth, have been ambushed by the evil magicians, the Dire Wraiths. The Solstar Order has prevailed and are now seeking out their scattered enemies.

One of these knights has followed the trail of the Dire Wraiths all the way to Earth. This one the Dire Wraiths fear more than all the others. This one has hounded them and kept them underground for centuries. This one alone could wipe them off the face of creation…

…

Even he must be careful. The Dire Wraiths can assume any form they wish.”

So says the original Rom promotional ad Parker Brothers shared with the 1979 Toy Fair, the first ever mention of Rom’s mortal enemies the Dire Wraiths. They’re described here as “evil magicians” in a bit of ad copy that may have sounded super cool 40 years ago but now sounds plain goofy. You might as well say “evil mimes.” “Wizards” or “warlocks” would have been more inspired choices, but actually, given the language of the rest of the ad, I can think of an even better description.

“Arcane terrorists” is the two word phrase I’d use to best describe the Spaceknights’s foes. Perhaps the mention of terrorism would have been gauch in an advertisement for a children’s toy, but regardless, that’s what we’re dealing with here, as the language makes plain. These are foes who “ambush” the Spaceknights, but are unable to sustain a long term engagement; instead they’re “scattered,” kept “underground.” These are enemies who do not announce themselves with uniforms; instead they “assume any form they wish.”

Most importantly, whatever is behind the nature of this conflict, it’s not enough that the order of Spaceknights defends themselves from the attack. They have to suppress the Dire Wraiths, force them underground, and track them — hound them — across the universe, all the way to another planet. The final, ultimate, goal is to “wipe them off the face of creation.”

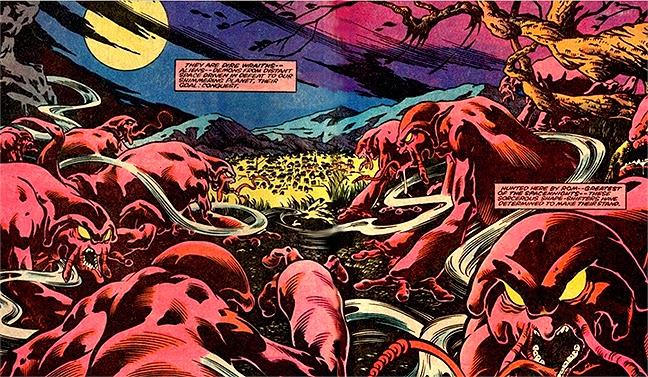

This extreme level of prejudice would carry over into the Rom comic series, and while in the toy ad the Dire Wraiths could plausibly be members of a sinister organization, in the comic they’re explicitly an entire race of creatures. Yikes.

26 issues into the series, Rom tries to destroy Wraithworld, the planet of the Dire Wraiths. The Spaceknight brokers a deal with Galactus. He tells the devourer of worlds that he’ll find him a planet to consume, if Galactus spares Rom’s homeworld Galador. Galactus accepts, and if Wraithworld’s energy had not proved so distasteful, the Dire Wraiths’s entire planet would have been obliterated.

Wraithworld is uninhabited, but it is because “vengeful Spaceknights” displaced them, “driving the shape-shifting populace to waiting ships.” Galactus isn’t the biggest “g” word looming about this story. If we attempted to map this dynamic to any real world conflict, the implications are horrifying. Luckily, maybe we don’t have to. Rom is mostly a comic about a cool looking robot guy who fights evil shapeshifters, right?

Still, are there any consequences to consuming stories who tell us an entire race can be purely evil, even if that race is purely fictional? How should we engage with such media? What expectations should we bring to it?

To even begin, we have to go back.

War in the Golden Age

WWII swept through the comic book industry in the 40s. Even months before America’s real world involvement, characters like the Shield and Captain America appeared on the page, punching enemy spies and even Hitler himself. After Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor, swaths of old and new characters alike joined the war effort, taking their fight to the Axis powers on the page and in the panels.

It’d be fair to equate most of these war stories to propaganda, and with villains as evil as the Nazis it’d be ridiculous to fault the creators and publishers all that much. Despite this, comic books were initially capable of conceptually separating Nazis from the German people. Paul S. Hirsch, in his book Pulp Empire, tracks the changing attitudes towards the racialization of America’s enemies in comic books. Early on, it wouldn’t have been uncommon to see a sympathetic, anti-fascist German in a comic book, juxtaposed against the sinister, sometimes bafoonish, Nazis themselves.

Comics meanwhile portrayed the Japanese as inhuman: as “Yellow Peril” stylized monsters, or jaundice skinned vermin men. In the world building of these comics, American soldiers were racially superior, capable of easily dispatching large numbers of inferior, smaller soldiers. These attitudes and those towards the Germans were not a result of any concerted effort, but rather a reflection of the beliefs and prejudices amongst the creators and the American people at large.

Then, enter the Writer’s War Board, a civilian run but government supported organization that served as the United State’s premier propaganda machine during WWII. The WWB decided comics were a useful tool to influence the mind of the American citizen, if written correctly. That “if” is important. The WWB determined that a comic reader should not see any separation between Nazi ideology and the German citizen. Instead, they stressed the emphasis should be that Germans — ALL Germans — were inherently violent and warlike.

The WWB also objected to the depiction of the Japanese, though not due to the propagation of racist, orientalist imagery. Rather, the WWB worried that readers would get the false impression that the war in the Pacific could be easily and quickly won. Like with the Germans, they said the Japanese should be inherently fascist and warlike, and should represent a substantial threat that needed to be overcome.

The WWB pushed publishers to include these specific characterizations in comics. They believed that stoking hatred towards the US’s enemies was necessary in order to ensure victory, eliminate fascism, and sustain a lasting postwar peace around the globe.

Cold War Comics

War comics lost popularity postwar, and the WWB disbanded. Superhero comics lost popularity too. Instead crime, horror, and romance stories dominated the stands domestically. Internationally the US began to distribute specially produced propaganda comics which depicted the North Koreans as barbarians, and Joseph Stalin as a sinister octopus strangling the world. When commercial comics did tackle war stories, many publishers didn’t treat the Korean War with anymore subtlety than WWII, the Japanese traded out for North Koreans.

There was one prominent, dazzling, exception: EC Comics. While the publisher was best known for its horror and crime titles, EC also produced war comics so politically subversive that the FBI began to monitor EC Comics publisher Bill Gaines. Cartoonist Harvey Kurtzman edited and researched two of the titles considered the most controversial: Two-Fisted Tales and Frontline Combat.

Kurtzman’s comics mostly didn’t rely on crude Asian caricatures. The story and art often depicted the North Koreans as humans who could think and feel, and loved and cared for other humans. The enemy here was not pure evil. They feared the American military and fought to survive. Both sides struggled to keep going, pushed forward by machinations beyond their control.

“Corpse on the Imjin,” published in 1952, is a famous example of these stories. The wartime violence depicted in this comic is radically different than the war comics of the 40s. While the American soldier defeats his North Korean opponent, nothing about the victory is glorified. The story treats it as a murder you’d see in one of EC’s crime comics, as the one soldier manically drowns the other. The narration describes the scene in second person, as if to implicate the reader.

“Suddenly your mind is quiet, and your rage collapses! The water is very cold! You’re tired…your body is gasping and shaking weak…and you’re ashamed! You stumble and slosh out of the river and run…run away from the body in the water!”

The FBI and army intelligence feared such stories might cause American soldiers to ask too many questions, or even to refuse orders if it meant they’d need to fight communists. However it wasn’t the FBI that would bring down Bill Gaines and EC Comics. Fredric Wertham and the Comics Magazine Association of America (CMAA) did that.

The story of Wertham and the CMAA is well known or better found elsewhere, but two aspects to it are notable here. Firstly, the CMAA’s restrictions on violence and gore made it so accurate depictions of war in a comic book would now be nearly impossible.

Secondly, Wertham made at least one valid point in his screed against comic books: they were racist. We saw this in the depiction of Asian soldiers, but also in countless comics featuring BIPOC folks in America and abroad.

One of the CMAA’s stipulations declared that “ridicule or attack on any religious or racial group is never permissible,” and while that sentiment is nice, it was oddly enforced. When EC Comics produced a science fiction story featuring a surprising, but positive, portrayal of a Black astronaut, the CMAA cited this standard to reject the story.

Going forward, publishers usually took the easy route by predominately featuring white characters.

Marvel Comics vs Communism

While war comics still existed into the sixties, the CMAA’s restrictions removed their claws in terms of both realism and propaganda. Additionally, the Vietnam War became the first nationally televised conflict. Cartoonish depictions of war may have convinced readers before, but now they would clash with real images seen onscreen.

One publisher did crack the code: Marvel Comics. Stan Lee, Jack Kirby, Don Heck, and company often pitted their new superheroes against the “red menace,” or against villains coded as such. Thor fights the North Vietnamese and a Chinese communist supervillain. Iron Man builds his first suit in Vietnam, while held captive by a North Vietnamese guerilla leader. Not long after the Bay of Pigs, Magneto uses nuclear weapons to threaten a fictional country in Latin America. In a separate fictional Latin American country, the Fantastic Four and Nick Fury help the CIA squash a revolution that threatens American interests.

In Marvel’s fantasy Cold War, American superheroes were powerful, erudite, rugged, and complicated, at least compared to other prominent superheroes of the time. Marvel characters enjoyed a sense of interiority. Tales of Suspense #39 is a story about a man wrestling with a newly inflicted disability, his only recourse to house himself inside a war machine. As Stark dons the first Iron Man suit, his thoughts float above his head: “My brain still thinks! My heart still beats! But, in order to remain alive, I must spend the rest of my life in this iron prison!!”

But while Tony Stark is presented as thoughtful and multifaceted, the Vietnamese characters in “Iron Man is Born” are not. The antagonists are 2 dimensional brutes, with arched eyebrows, big teeth, and yellow skin reminiscent of the old Timely Comics Japanese soldiers in the 40s (the CMAA somehow found nothing objectionable here). The one sympathetic Vietnamese character, Professor Yinsen, exists to prop up Stark. “My life is of no consequence!” he says in a moment of metatextual irony, “But I must gain time for Iron Man to live!”

Let’s compare Iron Man’s debut to two war comics out the same month. Neither All-American Men of War #94 or Our Army at War #125 come anywhere close to current events, both taking place in WWII. Neither comic portrays the enemy to any large degree at all, instead focusing the vast majority of page space on the protagonists, who fight against mostly impersonal planes, tanks, and oncoming bullets. The difference is stark (pun not intended).

This fit right into Marvel’s brand. Marvel presented dynamic superheroes against the backdrop of the world outside one’s window. Spider-Man and the Fantastic Four lived in New York City, not some fictional place like Gotham, and so similarly Thor and Iron Man could fight the real life enemies of America. Marvel’s approach here held similarities with some 40s comics featuring Nazis. Where uninfluenced by the WWB, Nazis were written as irredeemably evil, but other Germans could be good. The Vietnamese could also be good if they chose, but if they be communists, well, they were immoral to the bone.

Nazism and Marxist revolutionary thought are, of course, different beasts, but the common American may have viewed them the same. That certainly seems the case with Lee and Kirby. In the Thor story “Into the Blaze of Battle” (Journey into Mystery #117), the main antagonist Commander Hu Sak guns down members of his own family, screaming, “You do not matter! Nobody matters! Only the communist cause is important! People mean nothing! Human lives mean nothing!” Communism here is reduced to a sociopathic killing ideology and nothing more.

The story hits some of the same beats as one of Kurtzman’s war stories published more than a decade earlier. “Dying City!” (Two-Fisted Tales #22) follows a young Korean man named Kim who travels north to enlist with the North Korean People’s Army against his family’s wishes. Kim believes communism will free the world, but his lofty ideals are brought crashing down when North Korean bombardment destroys his home, kills his family, and blinds him. What’s notable is that while this story, too, is anti-communist, unlike the Thor story it actually engages with a conception of communism slightly more generous than “evil bad men.”

Before the catastrophe in the climax, Kim says:

“Times are changing! Today, the youth of Korea is joining the march of Russia and China to stamp out the enemies of the people! …What are a thousand lives now compared to the millions of years of future happiness!”

We can compare Kim’s speech to Hu Sak’s in “Into the Blaze of Battle!” Both use abstractions to justify killing, but the former is founded in idealism. Kim believes his actions will result in a net good, while there’s no indication of the same from Hu Sak.

While communism itself is still demonized, the story in Two-Fisted Tales allows that someone can be human and communist at the same time. The ideology is not a virus that overrides one’s morality, as it is portrayed in Journey into Mystery. Kim is not ethically reprehensible; he is foolish and mistaken.

This low bar, as a reminder, was enough to garner the FBI’s attention. To the US domestic security apparatus, any humanization of communists was dangerous. In this way, 60s Marvel Comics effectively played ball.

ADWAB (All Dire Wraiths Are Bastards)

The history and context of American war comics is important to any serious discussion of Rom Spaceknight (whether we need a serious discussion of Rom is another question, but you’ve read this far, so hey, just want to say, I appreciate you). Rom is a narrative concerned with war. There’s plenty of superhero action, science fiction, and supernatural horror as well, but the series always returns to the great war between the Spaceknights and the Dire Wraiths.

The comic thus intentionally or unintentionally presents its own assumptions about war. Throughout the series, Rom cycles through various attitudes towards the war that’s consumed his humanity, from righteousness to rage, from stoicism to despair, but one thing remains constant: the Dire Wraiths are pure evil.

This premise is never questioned, even when the occasional good Wraith pops up. In Rom #17, Rom meets a Dire Wraith who has settled down and started a family. He learns to love and feel human emotions, and for a moment it seems like this shakes Rom’s beliefs. After the Wraith’s human / Wraith hybrid son kills his father, the villain says, “I am a child of the Dark Nebula, Rom — I cannot know love or humanity!” Rom objects to this, saying,

“That is a lie which even I believed before today — never suspecting that Wraiths are made, not born! Isolated from his kind, your father threw off the evil of wraithkind — came to learn compassion, love, happiness! But the Wraith Elders dare not let their servile hordes dream that such an existence could be theirs! Thus they reinforce Wraith evil in their offspring, knowing full well that that which does not come naturally — can be taught, pounded into young minds until the unnatural becomes the norm!”

8 issues later in Rom #25, Rom meets another Dire Wraith who has managed to overcome his evil ways through the power of love, in the backup story “Love Will Tear Us Apart.” This story ends with Rom allowing the Dire Wraith to go free. “Humanity is a quality of soul,” he says, “not a bi-product of biology!” Maybe one time could be a fluke, but twice starts to be a pattern. What does Rom do with this evidence? Nothing. It’s in the very next issue that Rom hatches his plan to lead Galactus to the Dark Nebula to destroy the entire Dire Wraith home planet.

What are we to make of this? At first, it seems like the comic is going in an interesting direction, where we learn that the Wraiths are not wholly bad after all. You could imagine Rom learning to temper his hate, and working towards freeing the Dire Wraiths from their own fascist leadership. But this fruit never blossoms. Throughout the rest of the series, Rom goes inside himself to ask deep, burning questions — about himself, his allies, Galador — but zero page space is ever dedicated to questioning whether all Wraiths are truly evil.

By portraying a race who is inherently warlike, Rom Spaceknight does the old WWB guidelines proud. But I know, I know, you might be screaming this now, “the Dire Wraiths aren’t real! They aren’t real! It’s not like they’re dehumanizing a real life racial group, the Dire Wraiths are monsters for fucks sake!”

For anyone who thinks I’m overthinking all this, at least one guy agrees with me. John Henry Sain writes this of the Dire Wraiths in the issue #62 letters page:

“Do we just accept that they are all alike and if they are the enemy then they are all consummately evil to a single blackened soul, and any decent, freedom-loving, God-fearing citizen should hate them with all his heart? Total hate is necessary for total commitment to total war.”

He goes on to suggest that Rom should meet more good Wraiths, including an anti-war underground movement.

Had the editorial / creative team just asked John for some slack, reminding him they were a comic about a failed electronic doll, I couldn’t blame them. Instead, the answer we get is bizarre.

“John, there are times when a group of people may function more or less as a unit with no predominant differences in terms of attitude. Sometimes people with similar backgrounds will join together and often enough they unite against some sort of common enemy real or imagined. It has happened before.

In response to your comments about the Wraiths, it seems that their outlook and evil intentions toward the human race are so clear-cut and relentiess that we tend to think this is a unique situation.”

In the first section, it’s unclear whether they’re talking about the Dire Wraiths or people fighting the Dire Wraiths or what. The second part is also strange, as yeah, maybe it’s a unique situation but they chose to write it that way. John isn’t necessarily questioning how Rom should respond to the Dire Wraith threat given their actions on the page; he is questioning the worldbuilding, the premises and biases rooted in the story.

In part 3, we’ll look at where the Dire Wraiths sit compared to other fictional “hordes” in science fiction: is it all in good fun, or are there bad ways to do it?

— Ben Rathbone is the creator of this site, and its only writer. Don’t find him anywhere.

Leave a Reply