This article is the third in a 4-part (5-part?) retrospective on the original Rom series. Part 1 introduced Rom within the context of the other toy comics of the time and Part 2 explored the way the series handles its villains in the context of propaganda and war comics. I would suggest you read those, but if you pick it up here you won’t be too lost. Also see Who is the Real Rom Anyway?

“It’s all so insane! Like a nightmare! An alien lands on earth — and wages war on people I’ve known all my life — saying they’re not human at all, but really some bizarrely disguised, evil alien lifeforms called Dire Wraiths! …Rom says that his Neutralizer merely dispatches the Dire Wraiths to an other-dimensional Limbo…but to our human eyes it appears as if he’s murdering our friends and neighbors! …and knowing the truth — being the only one who believes Rom…is nearly mad!”

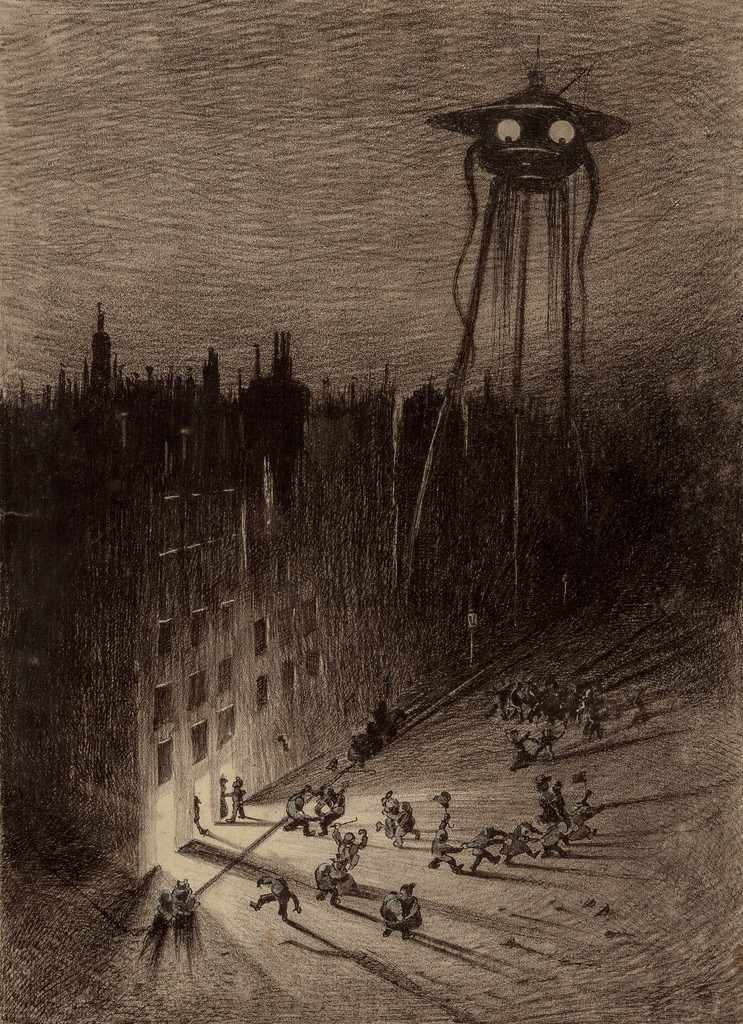

The first dozen or so issues of Rom, our titular hero doesn’t appear to be fighting an alien invasion. I mean, he makes the claim that he is, but we never see these aliens. As soon as the Spaceknight lands on Earth, he begins to fire on what looks like human beings. Rom leaves nothing but a pile of dust in his wake.

The US military responds with prejudice. Rom takes on gunfire, flamethrower, and tank shells. Later on, he defends himself against fighter jets in an aerial dogfight outside Washington, D.C. They really have it out for him. For a large chunk of the series he needs to fight on two fronts: the people he’s trying to protect, and the true enemy.

This is the Dire Wraiths’ strategy. They use their shapeshifting powers to position themselves within the planet they’re conquering. The highest of places and the lowest of places. They could be in charge of the Pentagon, or your next door neighbor. Anyone could be a Dire Wraith.

When we finally see the Wraiths’ true forms, they’re as hideous as you might imagine. Folds and flaps wrinkle the inhuman shaped monstrous bodies. Their mouths mandibles, and their backs hunched over in exaggerated deformity. Their eyes are soulless.

As we learned in part 2, Rom only pays lip service to the idea that there could be a good Dire Wraith. The comic decides around a quarter of the way through the entire run that Dire Wraiths are irredeemable.

There is a pleasure to taking in a story of good versus evil. We root for the rebel alliance without worrying about what Stormtroopers look like under the helmet, not just because we know what they represent, but also because it’s easier. Accepting the premise of a story to enjoy it is standard procedure, comes with the territory.

Let’s not just accept premises, however. Let’s shine a light on them. Poke at them until they crumble. Ask questions, get answers, and chew bubblegum.

(We’re all out of bubblegum).

The Science of Fiction

Most people know H.G. Wells as a father of science fiction, who among other books wrote War of the Worlds, the seminal work for which all subsequent alien invasion stories — including Rom — owe a debt. Wells, a prominent socialist intellectual, also wrote non-fiction: gigantic tomes on history, modern industry, and emerging technologies. But growing up, his life as an author wasn’t guaranteed.

In 1881, Wells’ family pulled 15-year old Herbert out of school to work. His father’s shop was failing in the wake of rapidly industrialized Britain. His Mom’s job as a maid failed to bring in enough extra income to survive. So young H.G. worked 13 hour days as a tailor’s apprentice at Hyde’s Drapery Emporium for 2 years, until he was able to return to school in 1883 and win a scholarship to the Normal School of Science in London.

Wells’ experience as a laborer never left him. He poured through books to make sense of the system of industry and capital around him. Through Darwin, he developed an understanding of progress, that biological beings adapt and change throughout history (it also briefly inspired some unfortunate eugenics type beliefs). Through Marx, he came to understand that society also changes and adapts to the material conditions it exists within. Throughout the rest of his life, Wells committed himself to the idea of a better world. He became a proponent for scientific socialism, advocating for a new social order that would liberate women, children, privately owned land, and the means of production.

This worldview, this propensity to dream of a better future, arguably is what turned his writing into the phenomenon that it was. “Science fiction” didn’t exist as a distinct genre until decades after the publication of Time Machine and War of the Worlds. Wells considered these works of his as part of a formless group of imaginative literature in the tradition of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein.

Years later, he’d reportedly write: “…the living interest lies in their non-fantastic elements and not in the invention itself. They are appeals for human sympathy quite as much as any ‘sympathetic’ novel, and the fantastic element, the strange property or the strange world, is used only to throw up and intensify our natural reactions of wonder, fear or perplexity.”

These “appeals for human sympathy” were not apolitical. War of the Worlds was written in the tradition of invasion literature, a popular genre which imagined a Britain militarily unprepared against a rival nation who suddenly developed new technologies (imagine France invading via hot air balloons that drop bombs, or Germany via stealth submarine).

These stories contained a sense of modern paranoia, but Britain itself was as likely to use military technology to invade a people as any other nation. One such case at the top of Wells’s mind was when Britain declared martial law against the aboriginal Tasmanians in 1828. Britain reduced the indigenous population of thousands down to just 220 survivors in seven years.

Wells takes this concept to its extreme; the Martian military doesn’t just have a leg up, but their incomprehensible technology makes them unstoppable. By vividly demonstrating a predatory, inhuman force brutally crush industrialized Britain, Wells shows his own country receive the same imperialist, colonizing treatment it’s responsible for around the world. Readers and critics adored it, the Daily News writing, “the imagination, the extraordinary power of presentation, the moral significance of the book cannot be contested.”

Probably noone predicted the book’s lasting influence. Science Fiction was just starting at the turn of the century, but by mid-century it was everywhere, in the form of pulp magazines and cheap paperbacks, ubiquitous ephemera which publishers churned out in order to be picked up and disposed of (kind of like another medium), and which readers often left unfinished. As a result of this ephemerality, perhaps the thing Wells argued against happened, and the fantastic elements took lead over the “human sympathetic” ones.

Ursula K. Le Guin famously said that “All fiction is metaphor. Science fiction is metaphor. What sets it apart from older forms of fiction seems to be its use of new metaphors, drawn from certain great dominants of our contemporary life…the relativistic and the historical outlook, among them.” Some of the pulp and dime paperbacks may try to relieve themselves of this lofty burden, but we oughtn’t allow them an out. Any author lives and breathes in the world, sees the society around them, and is moved by politics. Whether they want to send a message or not, one will reveal itself.

The “pulpiest” part of ROM Spaceknight is its villains. These monsters are intended as pure spectacle, esquisite in their depravity, evil, and hideousness. The form they take sends us a message about who our villains — the bad people who want to interrupt our lives and take our freedoms — are.

1) They could be anyone. Your neighbor, your friend, your family.

2) They’ve infiltrated the world at the highest levels already.

3) Once their true form is revealed, they’re irredeemably evil.

For the American public in the 20th century, this was all too familiar an enemy to have.

Red Scare, Blue Scare

In 1947, FBI director J. Edgar Hoover publicly addressed the House of Un-American Activities Committee at Congress: “The Communist Party of the United States is a fifth column if there ever was one. It is far better organized than were the Nazis in occupied countries prior to their capitulation.” Hoover warned that communists have and would continue to infiltrate transportation, communication, labor unions, the government, and Hollywood.

The idea of a fifth column — a group of people residing in a country sympathetic to an invading force, that help the force overthrow said country — gained popularity in America during the WWII era. The concept played an outsized role in policy, considering the level of evidence that there was any such element, and the outcome was 120,000 Japanese Americans forcibly relocated into concentration camps for 6 months by executive order.

When it came to communists, the result was first years of McCarthyism, where government employees and other public figures were ousted for largely unproven connections to communism (actual Soviet spies were mostly left undetected by the movement). Hoover carried his own crusade against the “communist fifth column” through the Civil Rights and anti-Vietnam War counterculture eras. He set up COINTELPRO to bypass laws against prosecuting people for political opinions. The program went on to disrupt a broad range of left-wing organizations deemed subversive.

Many COINTELPRO targets posed no practical threat to the state or public, and were only guilty of espousing left-wing views, or in many cases simply advocating for equal treatment under the law (often considered a left-wing view by itself). Civil rights groups, women’s rights groups, environmental groups, student demonstrators against the Vietnam war, socialist and communist political parties, Black nationalists — COINTELPRO approached them all with the same playbook: infiltrate, psychologically manipulate, harass in the courts, undermine in the public discourse, and if all else fails use illegal force and violence.

Martin Luther King, Jr. was by far COINTELPRO’s most famous target. Despite the fact that MLK never identified himself as a communist, Hoover was seemingly terrified that the CPUSA would infiltrate the civil rights movement. Leading up to and after the 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, FBI memos titled “Communist Party, USA – Negro Question” circled back and forth about MLK. One called him “the most dangerous Negro of the future in this Nation.” The same memo reminded its recipients that for such matters “it may be unrealistic to limit ourselves as we have been doing to legalistic proof or definitely conclusive evidence.”

The FBI soon began to bug MLK’s house and the hotels he stayed at. The surveillance only ramped up after the reverend criticized the FBI for not directing enough attention against white supremacist terrorists. The FBI allegedly sent King evidence of his marital infidelity, pressuring him to commit suicide before it was released to the press. Hoover and the FBI continued to surveil King up til the leader’s assassination in 1968. They even continued to try to tarnish his image for a year after the man’s death.

Another of COINTELPRO’s most high profile adversaries was the Black Panther Party. While armed community self-defense and revolution were part of the BPP leadership’s theory of change, much of the organization’s practical actions were peaceful and non-violent. Fred Hampton helped broker a non-aggression pact among the street gangs of Chicago, and the BPP’s breakfast program provided food to underprivileged children across the country. When an agent assigned to the San Francisco chapter reported no evidence of any violent plans against the state, Hoover responded by reminding the agent that his career depended on him supplying information that supported Hoover’s suspicions. Similar to the memo on MLK, Hoover once declared in a separate memo: “it is immaterial whether facts exist to substantiate the charge.”

While all of Hoover’s actions were not public information, his opinions on the threat of communism certainly were, and the FBI director enjoyed widespread approval for his entire career. In the last Gallup poll before his death, 75% of Americans rated his performance excellent (41%) or good (33%). Only 7% rated him outright bad. Hoover and figures like him successfully left a lasting mark on the American psyche for years and years to come.

H.G. Wells vs Stalin

In 1934, HG Wells met and interviewed Joseph Stalin.

During their talk, Stalin criticizes what he sees as a Utopian streak: “Of course, things would be different if it were possible, at one stroke, spiritually to tear the technical intelligentsia away from the capitalist world. But that is Utopia…can we lose sight of the fact that in order to transform the world it is necessary to have political power?”

The conversation turns into a strange battle of metaphors.

Stalin: “The transformation of the world is a great, complicated and painful process. For this task a great class is required. Big ships go on long voyages.”

Wells: “Yes, but for long voyages a captain and navigator are required.”

Stalin: “That is true; but what is first required for a long voyage is a big ship. What is a navigator without a ship? An idle man.”

Wells: “The big ship is humanity, not a class.”

Stalin: “You, Mr. Wells, evidently start out with the assumption that all men are good. I, however, do not forget that there are many wicked men. I do not believe in the goodness of the bourgeoisie.”

Throughout the interview, Stalin stays committed to the Marxist-Leninist line, that the working class must seize state power and oppress anti-revolutionary forces to defeat capitalism. Wells does not want to see things solely in terms of class warfare. He believes there are more and more breaks in the cogs of global capitalism showing everyday. He points to Roosevelt’s New Deal to argue that reform will eventually cause the old system to fall apart, and a resulting new planned economy will create the conditions for Socialism.

Wells was wrong. Capitalism did not fall apart. Reading the interview, you can sense his frustration as Wells optimistically attempts to find common ground, and chart a way forward that would unite all movements against private profit. While the two stay friendly, they clearly live in two different dimensions. At one point, Stalin remarks that the British bourgeoisie smartly act in their own interests by giving into small reforms. Wells replies dryly, “You have a higher opinion of the ruling classes of my country than I have.” At another point, as Stalin continues to assert that the best way to understand the world is in terms of the division between rich property owners and poor workers, Wells wildly claims to be “more left” than him.

Wells’ and Stalin’s desires for the world were not so different, but everything else about them was. It is a story as old as time, or at least the French Revolution. Leftist thinkers are united in their desire to overthrow the ruling class, but disagree on who’s included, how to do it, and what should replace it. That unfortunately leaves a lot of room for disagreement. For the J. Edgar Hoovers of the world, though, they’re all the same. All anti-Capitalist action and belief, however valid, is wrapped up in the methods — whether justified or extreme, real or imagined — of a select group. Hoover didn’t call out Soviets as the danger to America, he called out communists, socialists, and anyone critical of the status quo.

This is because the idea is far more dangerous than any fifth column of spies could ever be. If the working class truly organized against the capitalist class, the system that props up a select group of elites would fall. Hoover’s job, above all else, was to protect that system, and by red baiting and dividing every socialist adjacent group in the country, he succeeded.

So it makes sense that Rom Spaceknight’s enemies were 2-dimensional; thanks to the FBI the American public’s main enemies were also imaginary and 2-dimensional for the past 2 decades. As far as I can tell, this similarity is not intentional. It bleeds into the story from the creators, who are cultural conduits for the sentiments of the time. We can try to pick through intent versus accident, but the effect is the same. The characterization of the Dire Wraiths feels like propaganda, because it is formed out of propaganda.

Comic Book Villains

Some science fiction, and some comics, manage to present villains that are simultaneously diabolical caricatures and winks to the reader. Another alien invasion comic Marvel published in the 80s nails this balance. Strikeforce Morituri #1 published in 1986, the year the original ROM series ended. Like Rom’s own race on Galador, Earth resorts to extreme measures to defeat a wholly evil extraterrestrial force. Like with Rom, these measures involve infringing on the bodily autonomy of their soldiers. In this case, it specifically means granting humans superpowers with the tradeoff that they’ll die at any moment within one year after gaining the abilities.

The villlains in Strikeforce are — like the Dire Wraiths — irredeemably evil. Unlike the Dire Wraiths, they’re also satirical, and funny. The Va-Shaak manage to be comical baffoons while still being dangerous. Most interesting of all, though, is how they appropriate momentos from the worlds they conquer. They wear human iconography while they fight humans. You can recognize pop culture symbols Marvel comics owns, as well as national flags, etc. At one point, a member of Strikeforce Morituri breaks into a Va-Shaak treasure vault full of plunder from other worlds they’ve conquered. The loot is all recognizable comic book mementos from across publishers — Galactus’s helmet, the big penny in the Batcave, Captain America’s shield — as if the aliens are mirrors of us comic fans taken to the extreme, obsessive collectors to the point of sociopathy.

The Va-Shaak are not just stripping Earth of its physical resources; they are also mining human culture. They are colonizers through and through, calling to mind the way powerful nations have imperialized other nations for not just their resources, but their identities, throughout history.

In this way, Strikeforce is closer to War of the Worlds than Rom. It is not naive about the true shape of imperialism, and parodies it while crafting its villain. Unlike the Va-Shaak, the Dire Wraiths do not parody or call attention to the concept of what they represent. They’re meant to intrigue and titulate only.

Just like Strikeforce, though, Rom does interrogate the degrees to which humanity is willing to go to defeat their enemies. To do this, it investigates themes of trauma and disability, and of how the horrors of war rob a man of his humanity. It explores the dangers of empire, how even the most golden nation can slip into totalitarianism and despotism. It tests the strength of love against a world that causes so much pain and hate.

How well does it do? Find out in Part 4!

— Ben Rathbone is the creator of this site, and its only writer. Don’t find him anywhere.

Leave a Reply